NOTE: I started writing this article in June 2024 and then got busy; it’s now January 2026… it’s becoming a bit of a pattern.

We run Kubernetes at my day job (edit: no longer my day job), probably at least partially because of Maslow’s hammer but also because I truly think it’s the best tool for the job.

I’ll qualify that with something like “once your system gets to a certain size / complexity” and by that I probably mean something like “once your system doesn’t fit into the cookie cutter template provided by the various PaaS offerings”.

The nature of this threshold probably varies a lot between systems, but I think if you’re being honest with yourself, you’ll run up against it quickly in any project that involves a reasonably sized developer team or has to do anything other than provide a web page that’s fed by a database- and let’s be realistic, if your system isn’t talking to other systems, what self-serving problem is it solving?

So what is this threshold?

The line is pretty blurry in my head, but for me the threshold is somewhere around the time I find myself needing to orchestrate multiple PaaS systems (or other not-really-PaaS but equally vendor-locked systems) in order to go and fix a bug or write a feature (or provision the infrastructure to execute an some automated tests).

The folks building these 3rd party systems like to move fast and break things (and hey, don’t we all)- this is totally fine and I’m sure they think of everything they can to keep the developer experience a positive one as long as you’re operating within their ecosystem.

But they’re definitely not testing for (or even aware of) your team’s workflow in terms of integration between the different PaaS offering you’ve found yourself using purely in order to remain “serverless” (paying a nice, safe-feeling monthly bill with some vague promise of “support”).

And so you find yourself writing some bespoke tooling in order to make this sort of thing easier and it just breaks, at random- completely out of your control (due to 3rd party system changes) and is immediately the highest priority (if it means you can no longer deploy code until you fix it).

A great example of this is Expo dropping support for all but the prior version of their SDK when they release a new SDK- while this initially sounds harmless, they control the release of their Expo Go developer app (a critical part of developing on Expo); so if your app is still Expo SDK 48, you can no longer use the only available Expo Go developer app to develop your app for iOS (on Android you can still sideload an old APK fortunately).

Well at least they’re my problems

If you’re a startup, you’re trying to grow- if you succeed in growing, you’ll have a large team, so it seems inevitable that you’ll get to the point where your complexity has crossed the threshold (wherever it is for you) and the prior choices that you thought were going to help you go fast are now causing you to go slow.

For us, this threshold was when we had the following stack:

- Bitbucket building some Go components and SSHing them directly into EC2 VMs

- Bitbucket SSHing code for some Nextjs components, SSHing that to directly into EC2 VMs and executing builds on the VMs

- encore.dev pulling our private repo to its servers to build Go components and deploy them on our infrastructure using its own automation

- AWS Amplify doing the same, but for some Nextjs components

The latter two were attempts to get a fully PaaS approach for our system (primarily Go and Nextjs) and they were both failures in my opinion; build failures were opaque, runtime environments differed from local environments and control over deployment sequencing and other infrastructure concerns was nonexistant.

We changed to shipping all of this on Kubernetes (using AWS EKS) and realised a great benefits:

- I can spin up the whole system using Kubernetes for Docker Desktop on a developer’s laptop (basically exactly as I would for prod)

- This cuts out on a bunch of WOMM issues and makes it easy to iterate on cross-cutting system changes

- I’ve got a common protocol for producing and storing artifacts (Docker images and their repositories)

- The state of my entire system’s infrastructure has become code

- There’s a vast ecosystem of battle-hardened tooling for deployment and observability

But there was one benefit that has been the most valuable by far…

Breaking out of the shackles

Once our code was operating entirely in Kubernetes, the dependencies of our system had become greatly simplified:

- We need a managed Postgres database

- We need an internet-facing load balancer

- We need a managed Kubernetes cluster

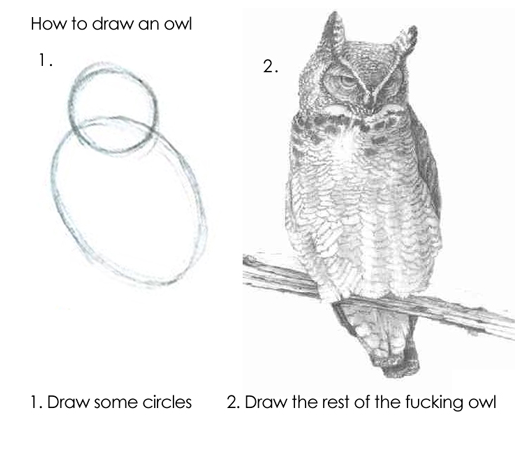

Of course to some, that third item might seem like a reference to this meme:

But I can say that has not been my experience; the resultant system is much more robust than the one we had before (with a lot less bespoke and fragile tooling involved) and the things I’ve learned about Kubernetes have been useful and will serve me in the future (as opposed to things I’ve needed to learn about bespoke tooling or uninteresting PaaS offerings which are ephemeral and just waste space in my brain).

There were two particular situations where we got to enjoy the benefits of Kubernetes; one of then was the migration from a third party OCPP server out of the Netherlands (I’ll write about that another time) and the other was the subject of this blog post.

So- our CTO came to me explaining that Google had come a-knocking and offered a generous amount of credit for GCP, could we use that in any way and run our services in GCP?

Well of course we can boss, we’re shipping on Kubernetes so we’re cloud agnostic and didn’t Google make Kubernetes? Surely they’re best-of-breed for this sort of thing!

Building out a plan

We had a few meetings with a few of the guys from Google here in Perth to run through our current AWS infrastructure and how that might best map across to GCP equivalents; here’s roughly where we landed:

| Requirement | AWS | GCP | Recommended approach |

|---|---|---|---|

| Managed Kubernetes | EKS | GKE | Autopilot “just works” |

| Managed Postgres | RDS | Cloud SQL | |

| Docker image registry | ECR | Artifact Registry | |

| End user management | Cognito | Firebase Auth | Keep Cognito (it’s low cost, migrating would be a lot of code) |

| Managed DNS | Route 53 | Cloud DNS | Keep Route 53 (it’s low cost, migrating domains is complicated) |

| Outgoing emails | SES | (no equivalent) | Apparently Google pushes you towards the likes of Sendgrid |

After a bunch of experimentation, I had a migration sequence that looked like it was gonna work and provided a few escape hatches if I needed to backout / abort the migration mid-way:

- (Assuming the new cloud infra is all provisioned and idling)

- Establish an IPsec VPN between the two clouds

- This was a very slow / error prone process

- Use GCP Database Migration Service to replicate the AWS RDS instance with the GCP Cloud SQL instance

- This was absolute magic (with a couple of small frustrations)

- Spin up the stateless services (request handlers and the like) in the new cloud

- Repoint DNS so that the new cloud is handling requests

- Spin down stateful services in the old cloud and spin them up in the new cloud

- Now the new cloud is doing all the work, against the old database

- Promote the Cloud SQL replica to master and repoint the services to that database

- Establish an IPsec VPN between the two clouds

It looks nice and clean and straightforward when written down, but it was not without challenges…

The complexities

Cross-cloud IPsec VPN

I had initially started out trying to provision HA VPN but getting all 4 tunnels described across two different cloud providers was a dry enough task that I kept making silly mistakes.

After a while I decided that it was only going to be temporary anyway so the redundancy wasn’t worth it and the Classic VPN would do just fine for my purposes.

This saved a fair bit of time (especially as I had to do it twice overall, once for the cloud development environment, once for production).

There was the usual amount of wrangling routes and security groups / firewall rules to get traffic passing, but mostly this side was as expected.

The biggest gotcha derailing my migration plan was realised once I started to factor in Postgres…

Cloud SQL access idiosyncrasies

In contrast to AWS RDS, GCP Cloud SQL does not provision a database instance actually within your VPC- it uses some of the IP range allocated to your VPC to route to a DB instance that’s provisioned somewhere in Google’s managed services network, and it achieves this with VPC peering.

It’s quite clever and I daresay it works for simple use cases, but it caused two unexpected changes-of-plan for me:

- Because Google control the far side (the Cloud SQL side) of the VPC network peering, you cannot choose to propagate the route for the network that the Cloud SQL

instance is sitting on through another VPC network peering or a VPN

- So I couldn’t have any intermediate states in my migration wherein e.g. my services were running in AWS, talking to a database running in GCP (without extra

work)

- This forced me to run an internal load balancer in the GKE cluster to provide access to Cloud SQL for services not in the immediate network

- And I also couldn’t share a single GCP-to-AWS VPN between my GCP non-prod and GCP prod projects (because VPC peering between those two GCP VPCs refused to

share routes for the Cloud SQL instance)

- This forced me to establish two IPsec VPNs (directly from non-prod to AWS and prod to AWS)

- So I couldn’t have any intermediate states in my migration wherein e.g. my services were running in AWS, talking to a database running in GCP (without extra

work)

Database Migration Service tedium

Earlier I said that DMS was magic- and frankly it is; but it took me a good few attempts to get things in the desired state and here’s why:

- A DMS job can only point at a fresh DB that isn’t a replica of anything

- The DB must be empty before it can be changed to a read replica

- Failed replication attempts leave the DB half-replicated, as a read replica

So, any time there was a failure (network failure, change in schema- anything) I found myself up for the following reset sequence (taking about 30 mins):

- Delete the DMS job + ancillary stuff and wait for deletion to complete

- Promote the new DB back to master and wait

- Empty out the new DB again

- Create a new DMS job

- Start the DMS job (which changes the new DB to a read replica)

- (rinse and repeat until the process is proven)

It would be great if it had some logic to do things like:

- Empty DB if not empty (need safety flag of course)

- If DB is already read replica, do nothing (instead of needing promote just to go back to read replica)

Uncertainties around DNS cutover and network stack behaviour on charging stations

In a utopian world, I’d be using a single DNS provider and running nice short TTLs and all the devices would respond quickly when I made DNS changes.

In reality, my DNS entries were spread across AWS Route 53 (sometimes with a nice low TTL) and Office 365 DNS (with the lowest configurable TTL of 30 minutes).

Even worse than all that though, the charging stations are a broad mixture of different vendors, some seem to be Linux-based and some seem to be more microcontroller-like, I’ve seen hints of Python libs, C++ libs, Java libs, ESP32 and more in the HTTP agents; this means there’s not really any consistency of behaviour across charging stations and vastly different network stack implementations.

On thinking through how things would play out, I came up with a few points to keep in my mind:

- Even with low DNS TTLs, we can’t be sure that the individual devices don’t cache entries for longer than the TTL

- Even if devices do honour TTLs properly, we’re talking about a long-lived WebSocket connection

- Without breaking the WebSocket connection, the device is likely to remain connected to whatever IP the DNS entry resolved to for a very long time

- Even if we break the WebSocket connection, we can’t be sure that the device’s retry loop doesn’t simply reconnect to the IP it was already connected to

I was really only left with one course of action: I’m going to have to be able to migrate the system from AWS to GCP but retain a presence for charging stations to connect to at AWS until all the charging stations are connected to GCP.

This sounds a bit daunting, but all it actually meant was adding a step to our migration process:

- (Assuming the new cloud infra is all provisioned and idling)

- Establish an IPsec VPN between the two clouds

- Use GCP Database Migration Service to replicate the AWS RDS instance with the GCP Cloud SQL instance

- Spin up the stateless services (request handlers and the like) in the new cloud

- Repoint DNS so that the new cloud is handling requests

- Spin down stateful services in the old cloud and spin them up in the new cloud

- Repoint the Kubernetes Service abstraction in AWS EKS to point to the equivalent Kubernetes Service abstraction in AWS GCP

- Promote the Cloud SQL replica to master and repoint the services to that database

Wrapping it all up

With the plan in place, I did a bunch more experimentation; soaking a free-standing non-prod instance of the system in GCP for a long time to see what I learned about the differences of GCP / GKE Autopilot (nothing notable, it’s pretty good), executing in entirety the migration process (but for non-prod), trying out rolling back half-way etc.

Feeling pretty confident, we scheduled the migration and went ahead with it- it was myself driving with my right-hand man assisting and frankly it was quite uneventful.

We followed the plan, got everything running over in GCP, saw that some charging stations were quick to connect to GCP and saw that as feared, some remained connected to AWS- but when the sun came up, it was all still operating and we were able to serve the usual rush of users charging their EVs as they parked them for work that day.

And that’s about all I can remember- if the blog post feels different for the last couple of sections that’s because they were added 18 months later, lol.

I’m gonna write more stuff soon I promise; I’ve got another good blog post on Quake 1 coming in the context of not being happy about using other folks ports and wanting to make my own (which I did, I’m excited to write about it- just gotta make myself start writing).