I started writing this article before I changed jobs, which was basically 6 months ago (in May 2023).

I’m gonna basically leave it as it was and just mark up the parts I got wrong / the parts that turned out differently as an exercise in I dunno, maybe forced humility / embarassment?

So, let’s dive into the article I wrote before I started the new gig and then follow it up with the last 6 months of reality.

The article from May

Sorry it’s been so long since my last post- I’ve done lots of interesting things since then, but I’ve been too busy to write.

Here’s a quick rundown:

- Still haven’t made any more music

- EDIT: No longer true, I made one track but it was a pretty constipated experience

- Set up CD for most of my disparate home Kubernetes stuff using Argo CD

- Lost interest in the FTP Game Jam as an excuse to learn Rust

- Refactored more of my RC stuff as an excuse to continue learning Rust (both native and embedded for ESP32)

- Got the folks at my (old) job excited about Platform Engineering

- Started a migration from Docker and bespoke tooling to Kubernetes (and, to be fair, a bespoke installer)

- Decided to quit my job (lol)

- In seriousness though, unrelated to any of the above, just time for a change

- If you’re desperate to know company / role details, check out my LinkedIn

I’m pretty sure there’s a meme about driving a Kubernetes migration and then leaving the company, but it’s fine- I’m pretty confident it’s the right choice and there’s a smarter guy than me who’s been working with me on it.

We’ve pulled together some cool but regrettably closed source stuff to make it more tractable for the nature of our customers (50-odd air-gapped on-prem instances); things like:

- An offline K3s installer that bundles a few useful bits

- Wireguard config and binaries to ensure Kubernetes control plane and data plane are easy to request firewall rules for (single UDP port between nodes)

- Docker image and Kubernetes manifest for a local private registry

- Support for RHEL7, RHEL8, RHEL9 and Ubuntu 16.04, 18.04, 20.04 and 22.04

- Some fun handling varying

glibcversions here

- Some fun handling varying

- All easily built using Docker

- An offline installer that bundles a new install / upgrade of our own software

- Go-based, makes use of the Helm library and Docker library

- Bundles all Docker images of our software plus the prescribed VictoriaMetrics monitoring stack

- Bundles all the manifests as Helm charts

- Executes / rolls back cleanly

I think if we can get it out the door it’ll take the complexity away from shipping the software and keeping it running (and allow us to remove a bunch of bespoke tooling that does an average job of things Kubernetes does for free).

Anyway, my post today is in the context of my new job (that I don’t start for another couple of weeks) and me refreshing myself on the my understanding of the stack they’re using in the context of the challenges they’re facing.

The state of play (as far as I can tell)

- Flutter frontend

- EDIT: I was wrong about this- it was React Native)

- Go backend

- AWS for infrastructure

- EDIT: This was correct but oh boy, in the worst way

The CTO and I were talking about encore.dev leading up the interview so I built on their chatbot example to make a ChatGPT variant to get some hands-on experience with the framework.

It wasn’t bad, I might do a post about it later on; but basically from the discussion with the CTO I infer that they’re either using Encore or they’re doing serverless AWS without a framework and finding that a challenge.

So I guess they’re either using Encore or they’re at least using Go (I assume serverless) and the CTO is trying to figure out how to reduce toil- fortunately Go is a language I’m very comfortable with so I think I can help out there.

EDIT: Sure not serverless

Without truly knowing the spectrum of challenges they’re facing, I’m planning to bring some of my experience with around a robust software development lifecycle to the table and drive adoption from the front (by doing):

- Keep the whole team abreast of the context around what we’re focused on right now

- I think we’ve managed to achieve this

- Keep tickets small with clean acceptance criteria (and functional test cases if possible)

- Make good use of a code repo

- Monorepo can be a nice way to avoid dependency hell

- EDIT: We got to this, but I didn’t do it alone; much thanks to a guy called Luke Gelmi who came in keen and excited and drove this to victory

- Monorepo can be a nice way to avoid dependency hell

- Have an effective pull request process

- Aim for small / focused PRs

- Aim for a quick turnaround on PRs

- Try to balance feedback between “objectively bad” vs “just not my style” (don’t squash creativity)

- EDIT: I think we managed to hit all these

- Make it easy to spin up prod-like environments for development and testing

- EDIT: Definitely did this and I think it was our biggest gain

- Make it easy to execute a suite of tests against a prod-like environment

- EDIT: More or less achieved this

- Have a suite of tests and execute them at sensible times

- When we commit changes to a PR

- When we merge a PR

- Every night (because external dependencies sometimes break!)

- EDIT: Got all this with compromises; orchestrating a test environment was hard, so unit / integration tests run on commit, end-to-end tests are run locally (manually) and nightly against the deployed dev / staging environments

- Store artifacts against commit hashes

- We might have to roll back and maybe that version doesn’t build any more (but we know it works)

- EDIT: We did this

- Store all prod-related configuration in a code repo

- EDIT: We did this too

- Drive prod-related deployments from that code repo

- EDIT: Yep

- Have the right observability for what we’re doing

- Are we busy enough to rely on metrics?

- Is our logging good enough to drill into problem areas?

- Are our individual transactions important enough that we need to care about tracing?

- EDIT: Well we’ve got Grafana and we’ve got some metrics but it didn’t go much deeper than that- structured logging / tracing is still a TODO (but this represents sensible prioritisation)

All of the above is underpinned by some good rules of thumb:

- Dependencies should be version-pinned

- There will be enough problems simply with external package repo availability

- EDIT: This was pretty much already in-hand thanks to

package.jsonandgo.mod

- Important dependencies should be vendored

- Remember when everyone started yanking their Python 2 packages from PyPI?

- Remember when Debian deprecated the Slim

dpkgrepo? - EDIT: This was prior experience that hasn’t been relevant as it turned out

- Artifact we deploy should be stored and versioned

- Makes it easy to redeploy it elsewhere, pick it apart for forensics etc

- EDIT: This was valuable and we did it

- Deployments should be immutable

- If we need to roll back, we should be able to do so by deploying a previous version

- EDIT: Same

- Deployments should be automated or close to automated

- It should be easy to execute a deployment, ideally easy enough that something else does it on our behalf

- EDIT: This has been hugely valuable

- Post-mortems we do should be truly blameless

- Individuals haven’t failed, our processes have

- EDIT: We haven’t been rigid at post-mortems; I’ve driven blameless as hard as I can, we’re just not very structured in post-mortems

Automation helps a great deal with this:

- Automated testing of components when their code changes

- e.g. unit tests / integration tests

- EDIT: Our coverage is definitely better here

- Automated storing of component artifacts when their tests pass

- e.g. Docker images / binaries

- EDIT: Well, we don’t push binaries if the preceding tests don’t pass

- Automated deployment of environments based on the state of a configuration management repo

- e.g. CDK / Terraform

- EDIT: Yep, thx Argo

- Automated testing of an environment when it’s deployed

- e.g. end-to-end tests / system tests

- EDIT: Well, sort of- we’ve got the nightlies

This all sounds very imperative and prescriptive but I’m a pragmatic guy and we’ll apply these things in a way that works for us- ultimately we’re trying to reduce toil and increase velocity but along the way there’ll for sure be some critical items that need muscling a certain way to meet milestones and naturally those items will be prioritised above all else.

I guess let’s say the above is a strategy but ultimately the needs of the business will dictate the tactics.

Excitement or anxiety?

I’m pretty comfortable with the soft-skills side of team leadership and I back myself technically, but I’m not strong with cloud so I wanted to try to get a feel for things before going in.

EDIT: Predictably, more challenges than I had catered for, but I guess I had sort of catered for there being more challenges than I had catered for so it worked out okay

Probably to a point of fault, I don’t like to plan and theorise too much before I start experimenting so I decided to slap together a demo repo to test out some concepts.

EDIT: This spike was largely a waste of time, we landed with Pulumi and Argo

It’s not complete yet, I wanna try to cover off on the common serverless concepts but so far I’ve really only got the following:

- A minimal Go backend that so far just responds with some context about the request

- A minimal React frontend that is presently nothing beyond Create React App

- Some CDK to deploy the above with the following concepts:

- Lambda for the backend

- S3 for the frontend

- ALB in front of the Lambda

- CloudFront in front of it all

- A resource group to track it all

I’ve tried to take my own medicine re: strategy above with a GitHub Action that does the following:

- Test all components as a gating mechanism

- Build all the component artifacts

- Ensure a “dependencies” infrastructure stack is deployed

- Basically just an S3 bucket for artifacts

- Deploy the component artifacts to the artifacts bucket

- Deploy the intended environment (e.g. dev, staging, prod) infrastructure stack

- Referring to the artifacts in the artifacts bucket

Right now the building of the artifacts and the deploying of the artifacts are artificially coupled because there is no configuration management repo to drive the deployment of the infrastructure stack; decoupling them should be easy though because the artifacts are “versioned” in the artifacts bucket so it would be trivial to tell the infrastructure stack which version to use.

The reality between May and December-ish

So, we’re back in realtime now- I’m not sure where to start; I guess lets go through some categorised dot-points…

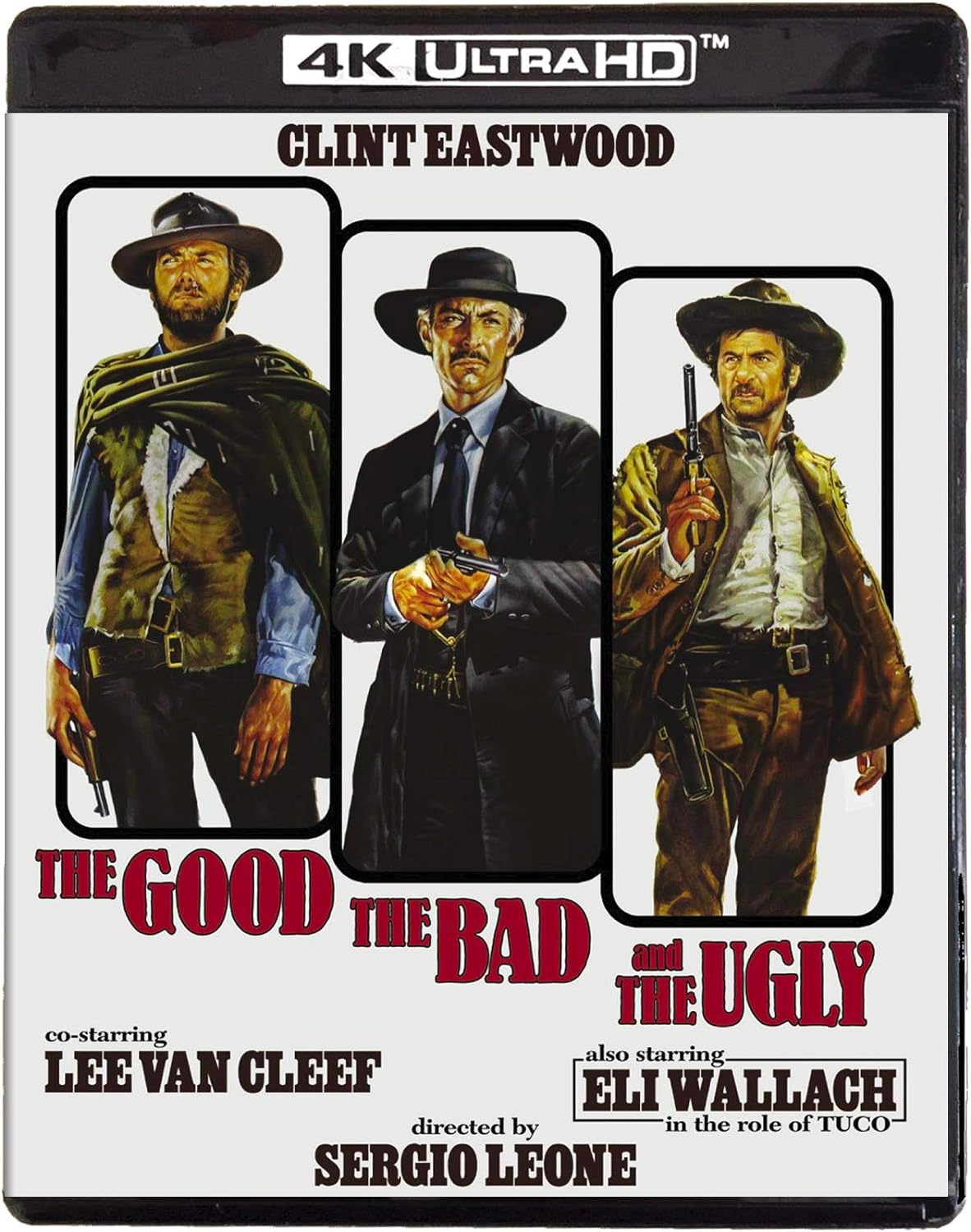

Clint Eastwood

- The team was excited and keen for some leadership

- The app + platform was (just) launched and mostly working (especially given the fairly complicated task it had)

- There were 3 cloud environments (dev, staging, prod)

- Commits to the master branch of each repo would cause (except for the mobile app) the build and deployment of the component in question

Lee Van Cleef

- Each dev’s local environment / local database was entirely self-managed

- So the completeness / correctness of your environment depends essentially on how skilled you are and how helpful the dev next to you is

- Everyone was developing on Windows

- No unit tests and no end-to-end tests (maybe one or two narrow-ish integration tests, but, to be fair, for some complicated parts of the system)

- A bunch of the senior devs (responsible for laying all the foundations) had got burnt out and left

- Two of them remained with about 2 / 3 weeks left when I arrived

- The breadth of the features of the system was (is) way too big for the problem domain

- As a result the system was large for how young it was, but nothing worked properly (due to the small team sprinting to kick something out the door but being swamped with too much functionality for an MVP)

Eli Wallach

- Levels of abstraction were low (and levels of repetition were high)

- I don’t know for sure, but I think this is a byproduct of folks not having confidence in their code changes (no tests) and probably a decent amount of ChatGPT

- It doesn’t seem that the architecture side of the software was thought about a lot and it doesn’t look like code

quality was pushed much in code reviews

- External interfaces would be a mixture of

CamelCaseandsnake_casewith no real pattern - Pointers would be used far too much (when not required) causing numerous nil pointer panics where they could have been entirely avoided

- The flow of data through the system / the way it affected the state of the model was all over the shop

- Some poll-based, some event-based, no thought given to concurrency problems / locking

- External interfaces would be a mixture of

- The “DevOps” capability was a part-time resource in another country, on a different timezone

- Very little work-in at all with the dev team (some of them didn’t know he existed); basically the opposite of DevOps!

- The 3 cloud environments were similar but not the same on account of being built entirely by hand

- Absolutely no IaC to speak of

- Absolutely no backups of all the hand-crafted snowflake resources

- The deployment mechanism for the backend was worrying- a Bitbucket pipeline would use the default image (gasp) to

build a Go binary for an unknown glibc version and literally SSH it through the front door of the backend EC2 VM where

it was run entirely natively

- There’s a lot to unpack here

- The glibc thing bit us when Bitbucket arbitarily updated (as you’d expect) the Go version bundled in their CI image (resulting in a Go binary that wasn’t compatible with the glibc available on the EC2 VM)

- The EC2 VM had to be open to the world to permit Bitbucket to SSH artifacts in

- There was no rollback mechanism; the proven, running artifact was ripped out of existence and thrown in the bin then the new one was started- if the new one didn’t work, you’d have to start typing real fast

- There’s a lot to unpack here

- The deployment mechanism for the frontend was even more worrying- a Bitbucket pipeline would literally SSH the code over to the frontend EC2 VM and then build it all there (somebody had already manually installed all the dependencies)

- We had dared to completely hand-roll Certbot stuff to handle LetsEnrypt cert changeovers

- Cron and slapped-together Bash- an accident just waiting to happen (and this is coming from a big fan of Bash)

The approach since then

I was immediately thrown into deep water (fair I guess, I had come on as the lead dev) and whether to sound me out or whether through necessity, the CTO had me wading through logs to get to the bottom of some prod issue within 2 days of getting there.

Fortunately Ops is my middle name and I’m familiar with AWS so finding the logs and the subsequent problem wasn’t too hard- it ended up being a silly and obvious nil pointer panic (one of the numerous that would plague us for a few months until we installed a handle-level panic recovery mechanism).

Repeatability

I was paralyzed for a week or two to be honest, just absolutely swamped in the sheer number of problems- when everything seems to be in a critical state, it becomes hard to work out where the right place to start chewing is.

We worked for a bit to get things halfway stable and get some grasp on what the team had promised to do in the near term and build a plan for doing that and then the obvious path started emerging.

We needed repeatable environments; these would stop us falling over ourselves, spending 2 days down the rabbithole chasing bugs that turned out to be stray stale data in local snowflake databases etc.

This was no mean feat and frankly it took months, but we had something workable fairly early; here’s where it landed:

- Get everyone off of Windows and onto Linux

- We had started off getting the devs out of native Windows dev and into WSL2 but it almost introduced more problems than it solved

- Moving to Ubuntu (batteries included) was well received and we saw a lot of benefit simply by writing code on the same platform we shipped code

- Devenv to handle the native dependencies (Go, Node, Android emulator, all sorts) and reduce the effort required to spin up a new dev (and reduce the odd issues introduced because e.g. Joe Bloggs has Node 16 and Jane Bloggs has Node 18)

- Docker Compose to orchestrate dependencies like Postgres, Stripe Webhook Forwarder

etc as well as the actual services

- We weren’t yet running containers in prod, but I had a pretty good idea that this was where we were headed so getting containers in dev was a good way to get everyone exposed

- Overmind to orchestrate native dependencies

- This was a necessity to help devs move fast with full-stack changes (enabling hot reloads etc)

- It did introduce a lot of complexity however (because full hot reloading meant running natively which means we lost the containerisation benefits)

So we ended up with a thing we call “the dev-env” (which is actually a name stolen from my last workplace and I daresay they weren’t the first place to describe such a concept) and two modes to operate it in (fully containerised or partially containerised with services running natively with hot reloading).

It’s been a big win- a developer comes in, spins up their dev-env which restores and migrates fresh databases, creates some fresh users (automated, but in the same way a user would signup, so free testing there), provisions some of the domain concepts that the system operates around and leaves them with some instructions on how to open the various services in their browser / emulator / mobile phone.

Automated testing

Now that we had repeatable environments, the next thing we needed was some level of confidence that the system worked as expected- we had behaviour spread between the mobile app, the NextJS web app and the Go backend so I opted for Python as an easy way to pull together some end-to-end tests.

I started out with a naive approach of just trying to cover every endpoint but some of the valuable interactions were spread across multiple endpoints and more than once service.

So, having already built out Python clients for every service (including Stripe) I basically built out some test cases that covered the most valuable user interactions and extended to a few common edge cases near them.

Just doing this exercise found heaps of stuff (and heaps of inconsistencies, essentially race conditions) and now the same tests (which have grown a lot) are a valuable part of any release (and the nightly test runs).

Unfortunately, I still haven’t been able to get entirely automated (e.g. on-commit) tests running in terms of entirely spinning up a clean and isolated dev-env and then executing tests against it mainly for the following reasons:

- The full dev-env is heavy

- Bitbucket is super constrained in the subset of Docker capability it gives you

So, a full clean end-to-end test run needs to be run on a dev’s workstation and the nightly runs happen against the already-deployed environments.

Maybe I’ll spin up Jenkins or TeamCity or something like that, but its basically got to the point where we’re getting 90% of the value and that last 10% will take (has taken already) too much time for not that much value.

Better deployments

It’s no secret that I love Kubernetes but I promise I’m not just a fanboi, truly I think it is great software- having wrangled as much Ops stuff as I have and been one of the key players in building out bespoke deployment tooling, you can see that the folks who built Kubernetes happened upon the same journey we did and came up with answers for all of it.

Things like being able to describe the desired state of your system as code, being able to diff the current vs desired state and have the system achieve it for you, automating the toil around rolling out new versions of services, rolling back on failure, doing something useful with Docker healthchecks (startup / liveness probes etc)- I really do think it represents the peak of generic tech for shipping things as containers.

So naturally, that’s where we went- I got everything bundled into containers, I got it all building and pushing to AWS ECR on commit and I deployed an AWS EKS cluster (using Pulumi for the base IaC and Argo for the “app” IaC) to ship it all on.

And I have to say, it has not missed a single beat and we simply do not worry about deployments any more; but here’s the best (and if you subscribe to the anti-hype, unexpected) part:

It’s cheaper to run.

Well, cheaper to run than what we had before- we used to have about 12 (small to medium) EC2 VMs spanning the 3 environments and assorted services and understandably because hand-wrangling Nginx is difficult if you wanna stack all your services on a single VM.

Now we’ve got 5 (smaller) nodes (probably only need 4) for all 3 environments and a stack of ancillary services as well as monitoring and I don’t need to worry about patching or anything.

So since I started, we’ve grown our service footprint a reasonable amount but somehow halved our monthly cloud spend and saved who knows how much developer time in putting fixes on top of fixes for bespoke deployment tooling (and dealing with the outages that come with that).

Monorepo

One of the first things I did when I started this new gig was set up about setting up a monorepo- but frankly I didn’t get very far, I got too caught up with trying to maintain throughput on features and releases while trying to improve our Way of Working.

3 months in, all I really had to show for in the monorepo was the dev-env, the end-to-end tests and some of the ancillary services that we grew after I started.

Luckily for me, we happened to hire an absolutely jet frontend dev a couple of months ago and he too believed in the value of a monorepo but unlike me, he wasn’t bogged down keeping the team ticking and keeping the lights on, so with very little guidance he was able to keep building out the rest of the monorepo to help us realise the dream.

He put in the hard yards getting the frontend code moved over and getting the dev-env working from the entirely new paths, leaving me with a bit of work to do in terms of getting all the Docker images building again and wiring in all the deployment pipelines and it was all done and dusted in about a month.

The win has been huge, devs have gone from opening 3 PRs for a single piece of work down to just 1 PR, any breaking changes can be looked at entirely in the context of the other changes for the same release, devs aren’t losing hours only to find the issue is because they were working on the frontend and had forgot to pull the latest backend etc.

Interesting findings

- I can operate for about 2 weeks going to bed at 3am before my body takes over and demands sleep

- No guarantees about what sort of a person I am to be around as I near the 2 week mark

- I can migrate a prod environment from EC2 to Kubernetes in the quiet period between the service going quiet-ish ( midnight) and before business picks up again (5am-ish) with minimal downtime (mostly just the no-mans land while DNS is in an uncertain state)

- I don’t need anywhere near as much test coverage as I thought I did (coming from a large Python codebase)- I think

this is because of the strongly-typed nature of Go

- Once this dawned on me, I became a lot less stressed, because I realised we weren’t in quite the bad shape I thought we were

- End-to-end test coverage is still important though, because complex behavioural / business domain-level bugs aren’t notably affected by things like strong typing in my experience

- I need to keep re-learning patterns about myself

- I’ll start out with a bit of “let’s just hack this thing in” mindset and it always, always grows into “okay this is more complex than I thought, time to write some tests” (I should really just start with the tests)

- The initially very daunting feeling of a large and foreign codebase and my natural inclination to hack and slash

continue to take a while to equalize

- It’s really hard to tell (without somebody to ask) what parts of the code are important vs not important, proven

and reliable vs flaky etc but until you know, you’ve really gotta treat lightly

- I’m always saying this, but I still, STILL don’t live it enough

- It’s really hard to tell (without somebody to ask) what parts of the code are important vs not important, proven

and reliable vs flaky etc but until you know, you’ve really gotta treat lightly

Other items of note

We’re building out a new service that I can’t really speak a lot about at present, but it’s gonna allow us to cut out a bunch in current software licensing and it’s been super exciting to work on.

I’ve been working closely with a somewhat junior Go dev that started the same day I did and it’s been really great to see him grow as a pragmatic Go developer by working on this new service (that doesn’t fit the typical mould of " web-based backend" and is more about complex interactions with devices deployed in the field).

I’ve been able to share some wisdom and guide the approach (and I’ve had to compromise on some items- I swear buddy we’re gonna need that FSM and the complexity will be worth it but hey, you win for now) and I’m proud of the shape its taken.

In closing

I’ll probably park the article here, it’s taken 6 months to write and its an almighty wall of text. All in all, I’m enjoying the new job and while it’s definitely a paycut (being a startup), the open / unsolved nature of the problem space and the (initially overwhelming) amount of opportunity to deliver some value has been super rewarding.